EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE

Discussion with or about everyday people living extraordinary lives

JAMES BUCHANAN EADS

Civil Engineer May 23, 1820- March 8, 1887

In “LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI Mark Twain wrote about “peculiar requirements of the “science of piloting” a steamship.

“First of all, there is one faculty which a pilot must incessantly cultivate until he has brought it to absolute perfection. Nothing short of perfection will do. That faculty is memory. He cannot stop with merely thinking a thing is so and so; he must know it; for this is eminently one of the “exact” sciences. With what scorn a pilot was looked upon, in the old times, if he ever ventured to deal in the feeble phrase “I think,” instead of the vigorous one “I know!” One cannot easily realize what a tremendous thing it is to know every trivial detail of twelve hundred miles of river and know it with exactness. If you will take the longest street in New York, and travel up and down it, conning its features patiently until you know every house and window and door and lamp-post and big and little sign by heart, and know them so accurately that you can instantly name the one you are abreast of when you are set down at random in that street in the middle of an inky black night, you will then have a tolerable notion of the amount and exactness of a pilot’s knowledge who carries the Mississippi River in his head. And then if you will go on until you know every street crossing the character, size, and position of the crossing-stones, and the varying depth of mud in each of the numberless places, you will have some idea of what the pilot must know in order to keep a Misssissippi steamer out of trouble. Next, if you will take half of the signs in that long street, and change their places once a month, and still manage to know their new positions accurately on dark nights, and keep up with these repeated changes without making any mistakes, you will understand what is required of a pilot’s peerless memory by the fickle MIssissippi.

I think a pilot’s memory is about the most wonderful thing in the world. To know the Old and New Testament by heart, and be able to recite them glibly, forward and backward, or begin at random anywhere in the book and recite both ways and never trip or make a mistake is no extravagant mass of knowledge, and no marvelous faculty, compared to a pilot’s massed knowledge of the Mississippi and his marvelous facility in the handling of it. I make this comparison deliberately and believe I am not expanding the truth when I do. Many will think my figure too strong, but pilots will not.” 1.

Painting by Martha Mudd Adrian from Hannibal , Missouri. Loved by her family and friends. Lost to us November 9, 2024.

Wind and weather. Ebb and flow. Majesty, treachery and tragedy. Sailing freer than free. Deep heartache. Life on the Mississippi never ceases to enamor. And disappoint. From great heights of emotion to supreme lows of sorrow, life on the great river demands attention to safety and survival. It demands respect. Whether on the levee or afloat we are in awe of its flowing nature.

To understand its emmense draw one must have lived on the Mississippi. Only one man truly understood the river from above and below. He was James Buchanan Eads. Whether standing on top of an arch inspecting the construction of his uniquely designed bridge or walking on the swift and silty river bottom, Eads more than any other man knew the river from top to bottom.

Early on, Eads learned the all or nothing, give and take, of the Mississippi. At thirteen (1833) Eads traveled with his family by steamer from Kentucky down the Ohio and up the Mississippi toward St. Louis. Along the way, a fire broke out in the boiler room. The ship sank. The family survived with their lives and nothing else.

The family finally made it to St. Louis and Eads began working in a St. Louis mercantile to help with family expenses. Eads had the good fortune of the owner taking him under his wing and encouraging use of his extensive library to study. Through this one man’s generosity, young Eads studied mathematics and mechanical design. Over time, he became an inventor, designer, and a self educated world famous engineer. All the while, Eads’ “draw” to the Mississippi never ceased.

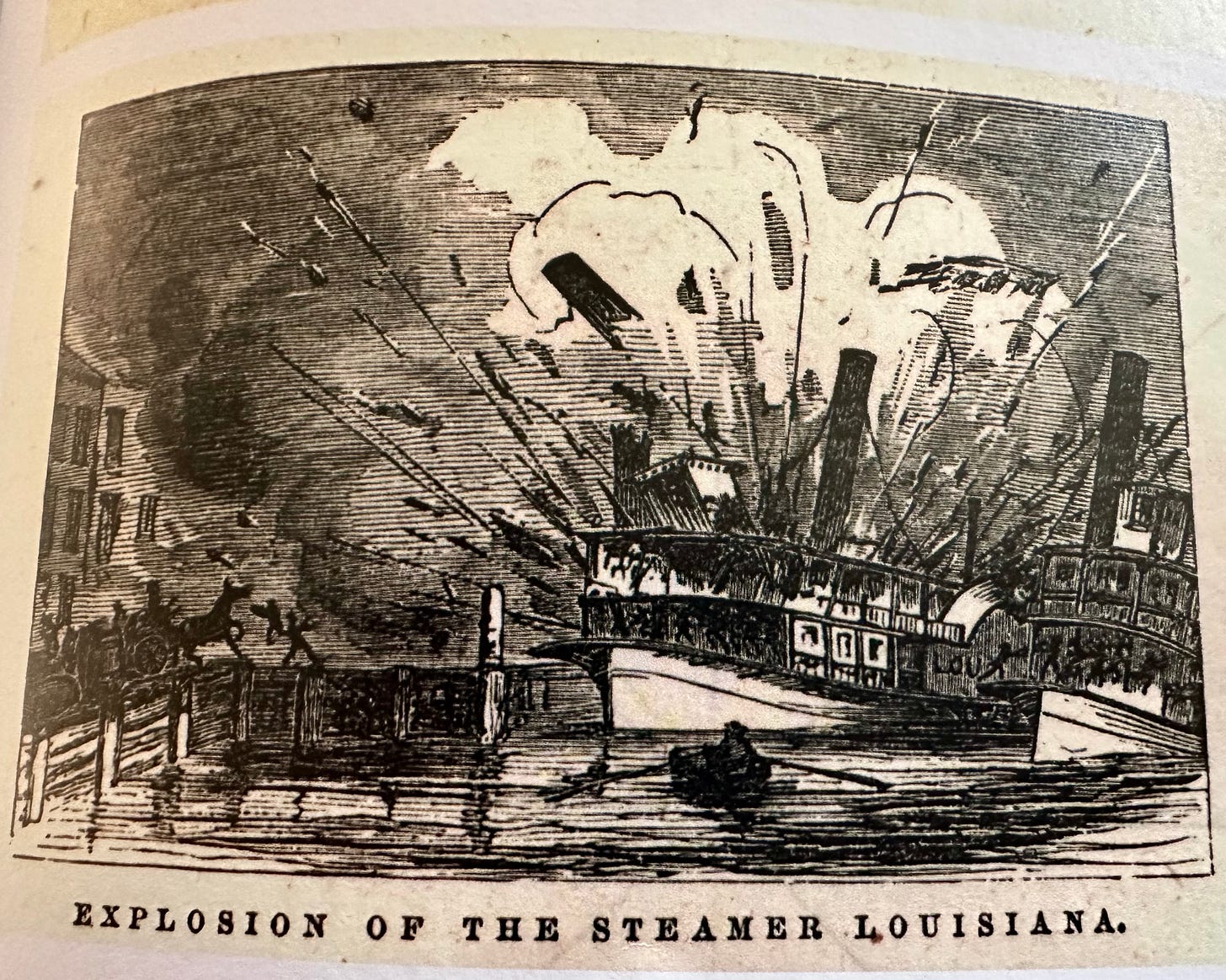

At twenty three (1842) while working on the Knickerbocker as a ledger keeper the steamer sank when its hull ripped open on a submerged tree. Again he survived with nothing but detailed knowledge of the lost cargo. Steamboats were notorious for sinking. More often than not a ship’s demise was caused by an onboard high pressure boiler explosion or a large underwater snag.

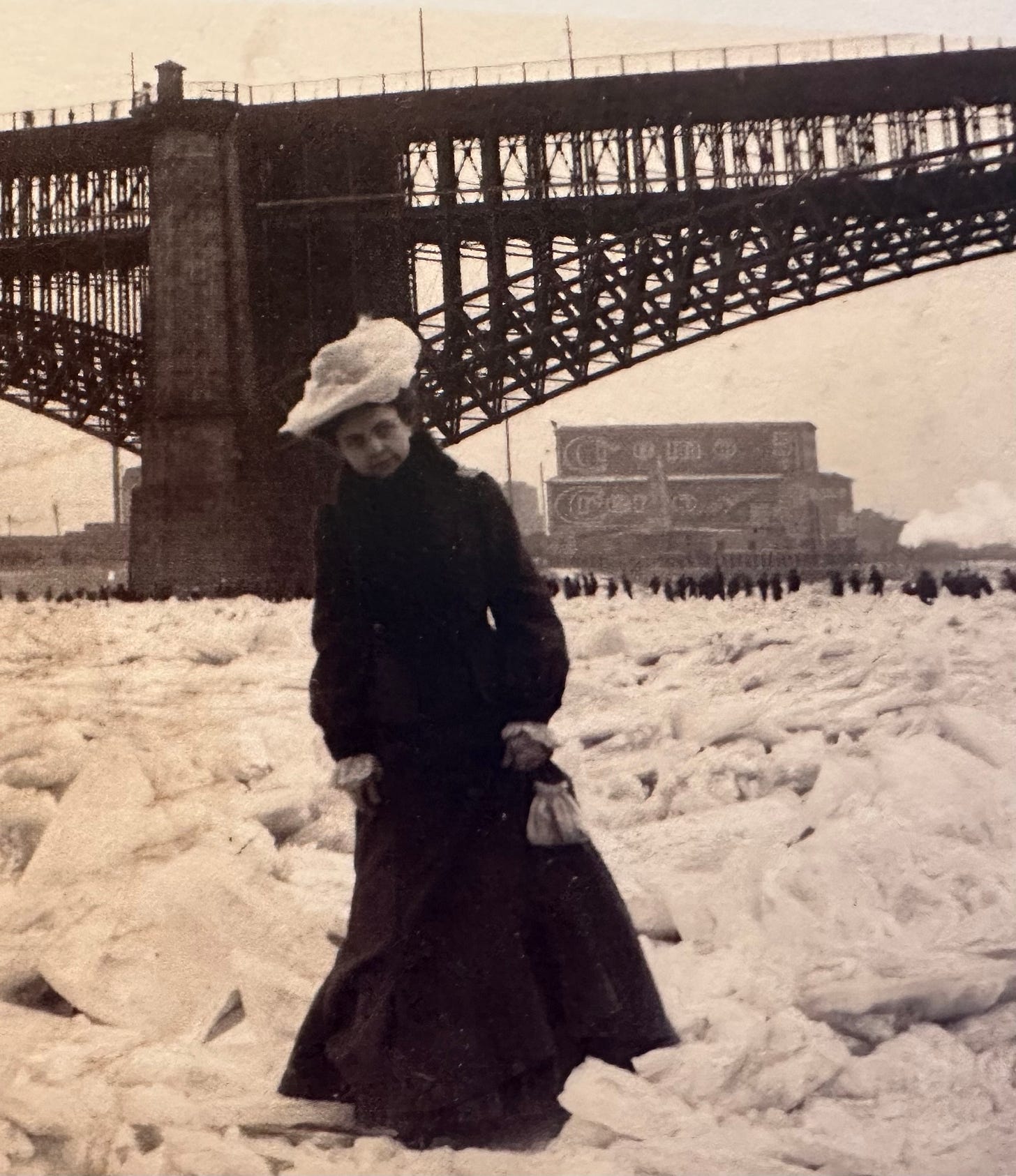

Fire wasn’t the only danger for steamers. Floooding and ice caused enormous problems also.

The frozen river, early 1900’s. From The Great River City, Andrew Wanko.

Ice Bridge over the Mississippi at St. Louis, 1873 Great River City by Andrew Wanko.

“Yesterday I went in company with some Ladies and Gentlemen, and we walked (across the river) to the Illinois shore. Don’t be alarmed, for the ice is 5 or 6 inches thick and they are constantly passing over with horses and loaded sleighs. Indeed while we were on the ice a man passed us with a sleigh load of coffee in sacks at a full gallop. The river is covered with skaters cutting all sorts of capers.” J. F. Sowell, 1845. 2.

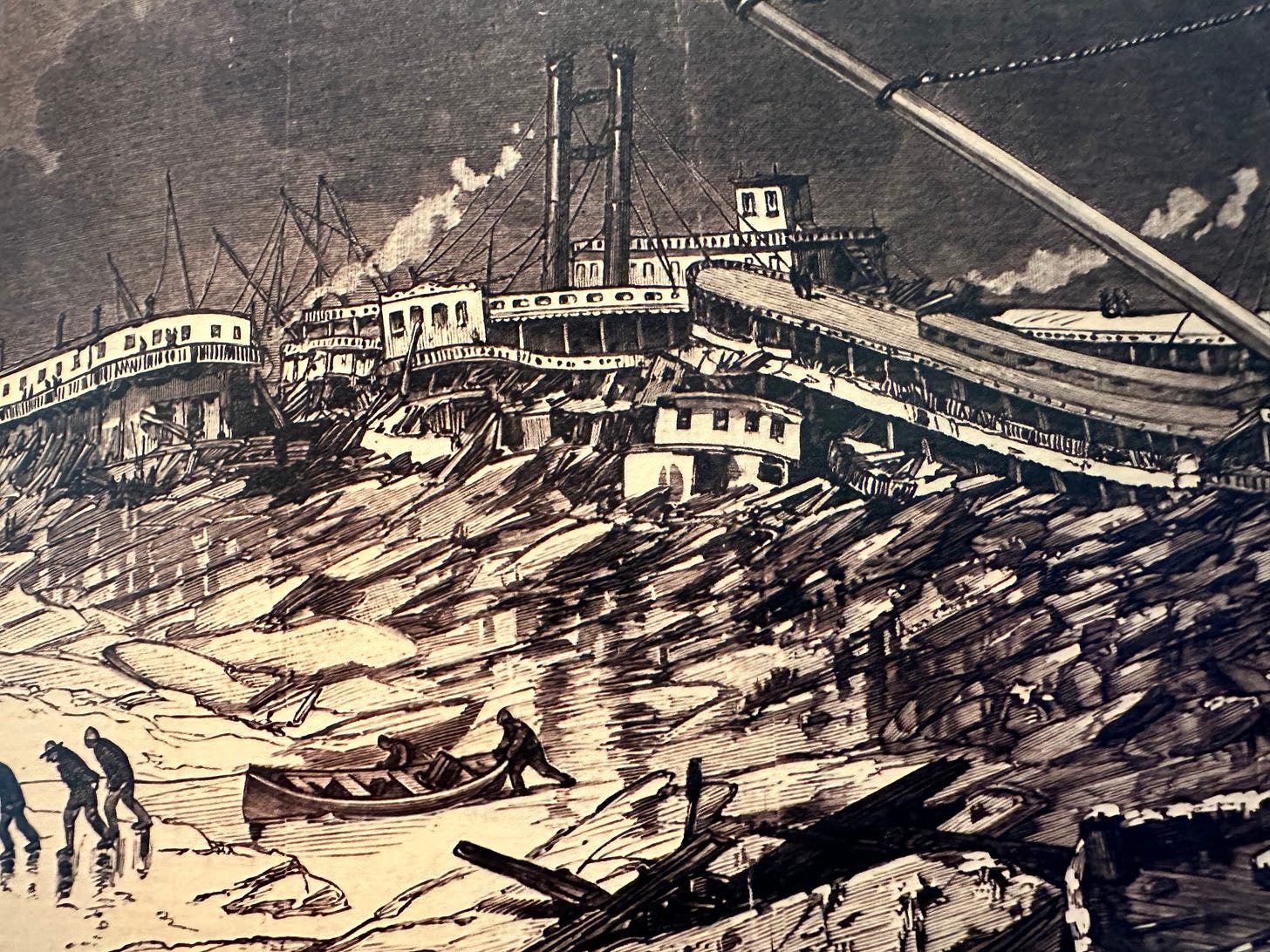

The Mississippi’s romanticism, adventure and awe turned to sorrow when an ice gorge destroyed dozens of steamboats in 1877. Somehow, small rescue boats moved in, out and around trapped steamers picking up stranded crew and retrieving as many valuables as their skiffs could haul. Thus, once again, depending upon one’s relationship with the river, the ice was either exciting or disastrous.

Destruction of Steamers at St. Louis, 1877. From Great River City, Andrew Wanko.

Eads’ experience on the main channel and inland waterways did not discourage his fascination with the science of the river. It only heightened his curiousity. Free time was well spent studying model steamboats and mechanical inventions.

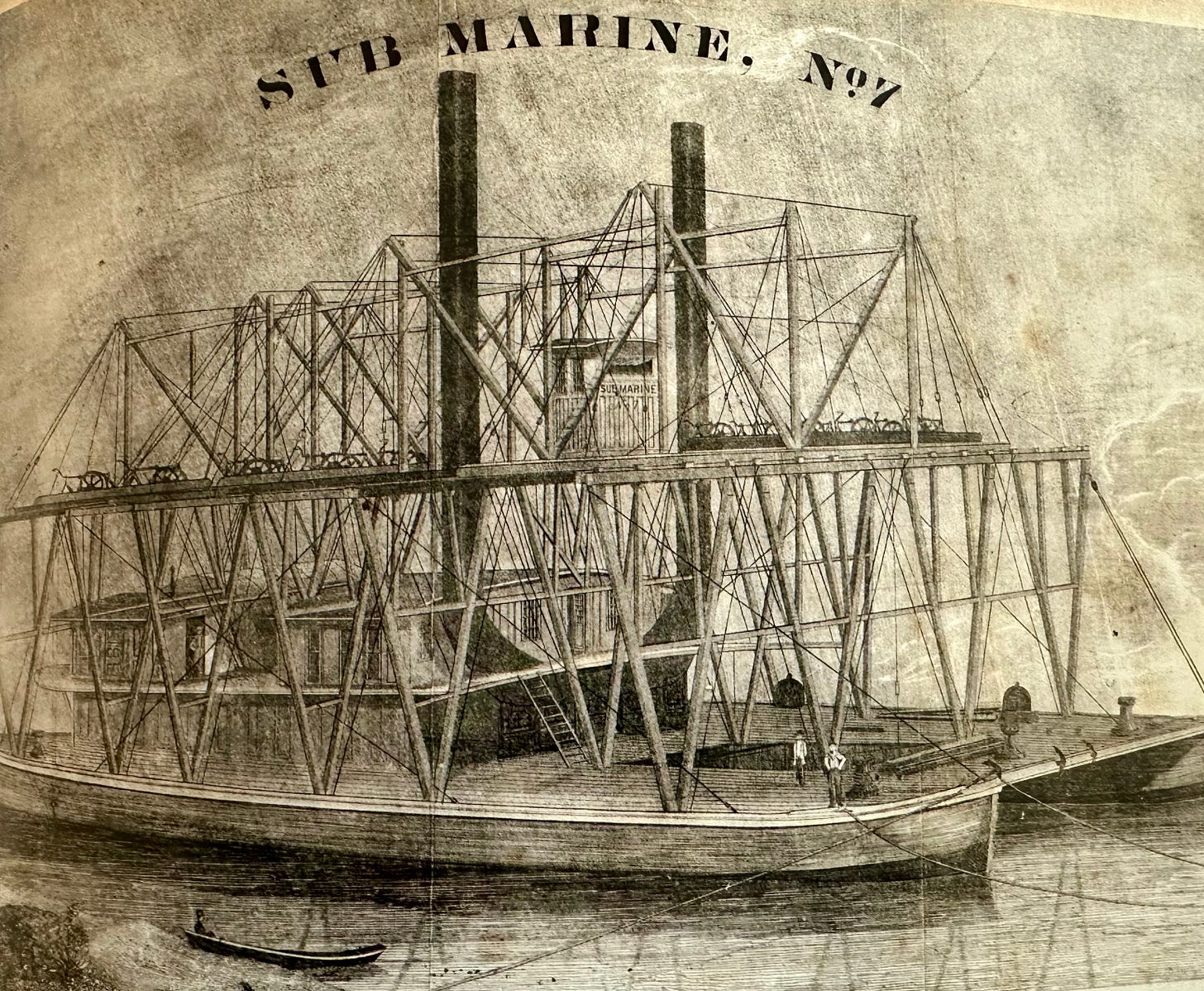

“(Eads) couldn’t stop thinking about the goods and wealth trapped in boats beneath the murky water. So, he drew up plans for a wreckage-salvage boat called a submarine complete with hoisting chains, pumps to remove river sediment, and a diving bell that could scour the river bottom.”

James Eads’ submarine, 1858. Twin pontoons with a winch between them to crank up recovered cargo or entire sections of downed boats. From Great River City, Andrew Wanko.

“Made from a tar-coated whiskey barrel with one end removed, the diving bell was a claustrophobic’s nightmare. Dangling lead weights pulled the bell to and fro nearly 500 feet across on the riverbed. At the lowest depth (65 feet, surprisingly no mention of decompression sickness) and with only a thin air-supply hose to keep him alive, the blind diver shuffled across the river bottom’s unstable sand battling hurricane type currents, whirlpools and (sand) boils from the river’s sediment. The diver would feel around for pieces of steamboat wreckage and winch them up to the surface to be examined.” 3.

Scouring down river toward New Orleans and up the Ohio River, then northward to the Missouri and Illinois Rivers, the salvage business found abandoned and sunken steamboats. Eads’ hunts gave him success never imagined.

“Eads made more than five hundred trips to the river bottom in his diving bell: few others were willing to attempt the dangerous but rewarding work.

The 1849 St. Louis fire, which sank twenty three steamboats just off the levee, provided Eads with a grand finale of salvage work, and by 1853 he retired (or so he thought) a wealthy man.”

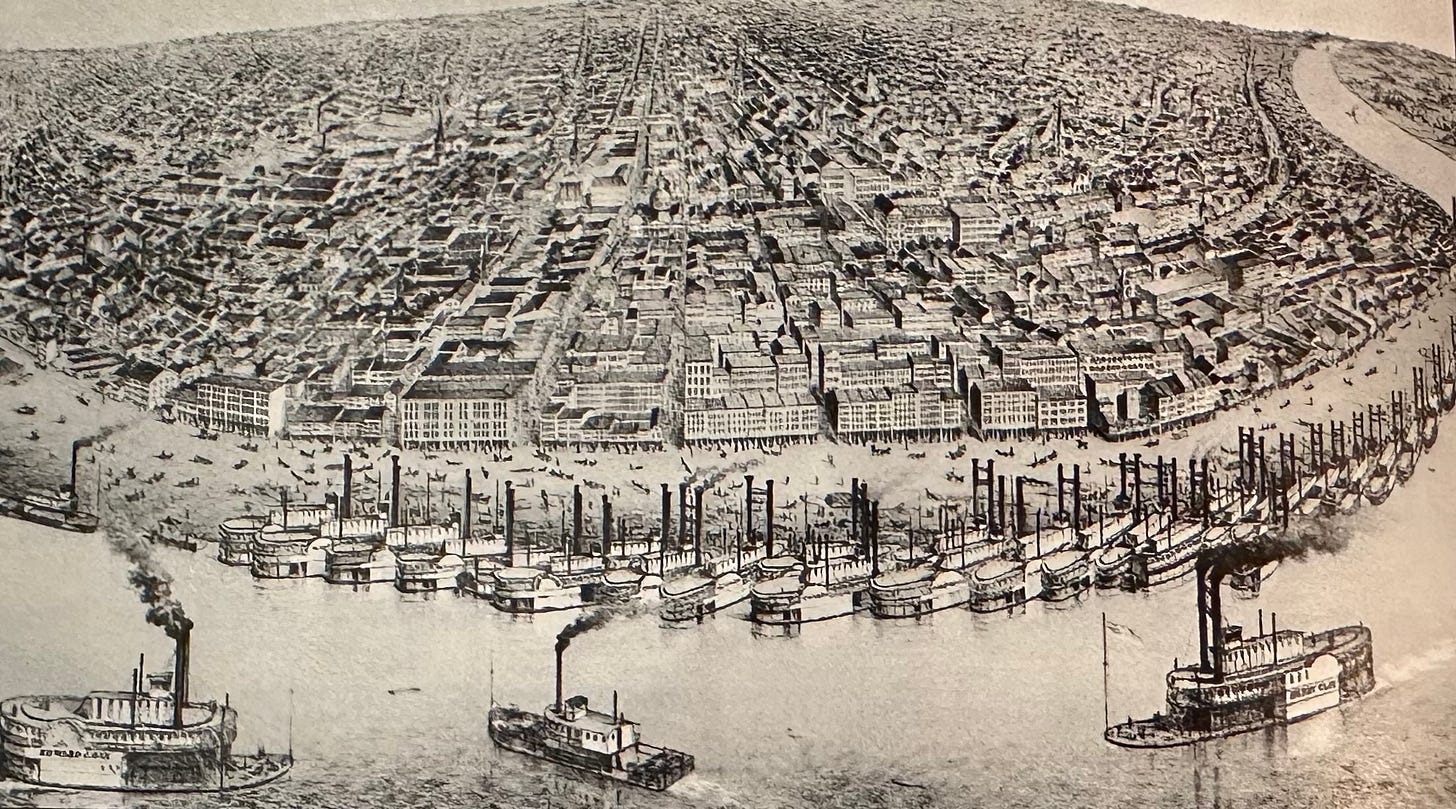

“From its founding in 1764 St. Louis was closely tied with the Mississippi River. The city shown here in 1859 became a vital connection for north, south, east and west.” Meet Me In St. Louis, A Trip To The 1904 World’s Fair by Robert Jackson.

While Eads was diving below the river’s surface, bridge builders targeted river towns up stream such as Bettendorf, Iowa and Rock Island, Illinois with the intent of steering all railways to Chicago. Wooden bridges were built mostly by opportunists who hungered for railroad dominance rather than quality and safety of design. Competition for commerce was fierce. Chicago businessmen stopped at nothing to circumvent St. Louis which had taken its place as the third largest city in the United States.

Wooden bridges up and down the Mississippi merged the east and west. Trains began to replace steamboat romanticism with a more modern industrialized notion of improved commerce and travel. But the bridges were not built to last. In one questionable case, a steamboat hit the Rock Island Bridge piling which caused an explosion that burned both ship and bridge.

Chicago based designers, with questionable intentions, slow walked St. Louis bridge contracts while plotting with major river ferry owners to expand their influence and commercial interests.

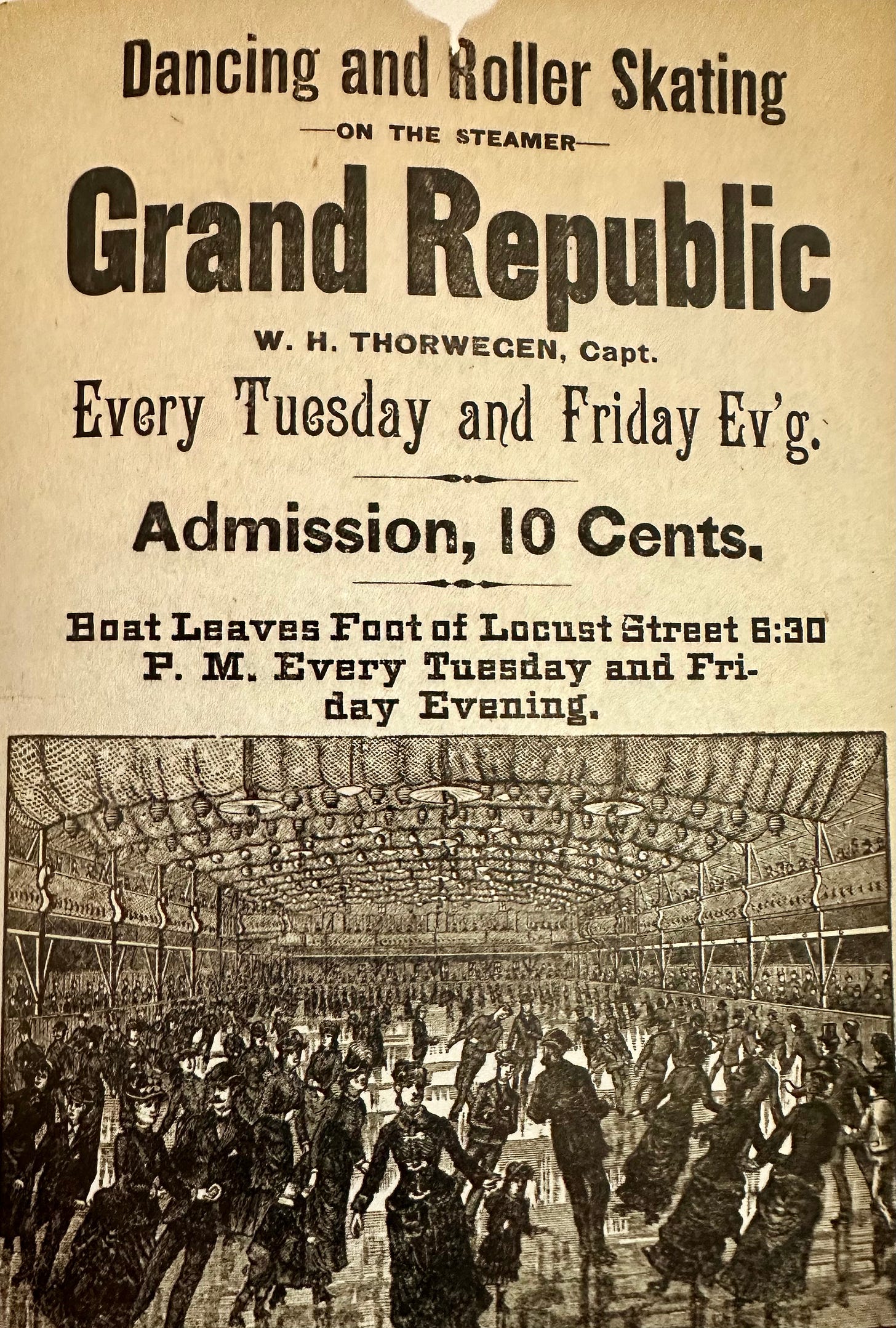

Many considered a steamer the foremost venue for leisure travel and entertainment. Boarding one of many docked on the levee excited both locals and visitors. So, train travel altered the city’s commerce in numerous ways but some things didn’t change. (After all, you can’t roller skate on a train now can you, dear reader?)

Roller skating aboard a steamer. From Great River City by Andrew Wanko.

Meanwhile, Eads was privately designing his own bridge while developing relationships with federal, state, city and private concerns. Conversation included Eads’ impressive art of persuasion and the discusssion always included the idea of a new and unusual bridge design with stability and longevity for generations to come.

THE WAR

Years of bridge planning and design were halted with the onset of Civil War. St. Louis was a central location for wartime hospitals, industry, commerce and planning. Union and Confederate soldiers, free and runaway slaves, money hungry carpetbaggers, legitimate and questionably legitimate businessmen, doctors/nurses/hospital staff, strategic war planners and, of course, politicians descended on the city.

“When the Civil War split the nation in two the Mississippi River was no longer just a waterway, it was a crucial military asset. Ocean going war vessels were at full strength but rivers were left defenseless. St. Louis was an important location for northern strategy on the war’s western front.” 4.

“When the United States erupted into civil war, Eads wanted to use his knowledge of the western rivers and his engineering skills to help the Union. In 1861 he wrote to Edward Bates, the US attorney general, to suggest that the Union needed to build a fleet of armored steamships for use on the river. Bates, who was from Missouri, summoned Eads to Washington to make the case for a river navy in the West. Soon after the meeting, the army advertised for bids, and Eads’s design won the contract to build warships. He promised to build seven steamships with iron plating within just sixty-five days. The ships were called ‘ironclads.’”

Ironclad gunboat. Notice slanted bow to offset attack. The iron plated structure made cannonballs explode without damage to the ship. Missouri Encyclopedia.

Because the country was at war supplies and workers were difficult to find. However, Eads’ ship building business, named Union Works, found 500 men, operated 24/7, and built 6 ironclads in 65 days.

The first of the gunships, the St. Louis, launched five weeks after Eads started work. Eads failed to build all seven ships in sixty-five days, but after one hundred days the last of the seven entered the Mississippi River. Eads wrote to President Abraham Lincoln : “the St. Louis was the first iron clad built in America…She was the first armored vessel against which the fire of a hostile battery was directed on this continent.” Eads’s ironclads were important in helping the Union to regain control of the Mississippi River. In August 1864, four of Eads’s ships helped defeat Confederate forces in the Battle of Mobile Bay. Armored steamships allowed the Union to resume shipping along the western rivers.” 5.

In addition to the ships, one of Ead’s many patents was for a turret designed to improve gunnery on the ironclads. The Missouri Historical Society archives includes numerous letters to and from Eads to Washington, DC and commanders aboard the ironclads. They suggested ironclad improvements. Eads was able to create a part or design an adaptation to the ships. The letters alos offered greetings for ironclad successes and even a thank you to Eads for the delivery of a case of Missouri Catawba wine to one of his favorite congressmen.

Memphis, June 1862. The Mississippi River Squadron crushes Confederate forces in a lopsided defeat witnessed by many Memphis citizens. Union victory leaves Vicksburg, Mississippi as the only remaining Confederate stronghold. From Great River City, Andrew Wanko.

St. Louis’ river position not only made it a supplier of boats and other weaponry that “pushed the war forward, but also became a fallback city for the war’s horrifying human toll. The brutal battles resulted in thousands of wounded. As smaller hospitals down river quickly filled, many patients were sent upriver to St. Louis on board hospital steamers. By 1864 the city had cared for more than 60,000 people, housed among at least a dozen makeshift hospitals.” 6.

THE BRIDGE

“Eads foresaw that railroads would be the main transportation system for the latter half of the nineteenth century, just as canals had been for the first half. To make St. Louis the major East-West rail center, a bridge was needed across the fifteen-hundred-foot, fast-flowing Mississippi. There was no precedent for such a bridge.”

“Business and political disputes loomed as the bridge concept became imminent. The Wiggins Ferry Company stood to lose its monopoly on moving freight and people across the river. Powerful railroad financiers were less than enthusiastic. Chicagoans believed that such a bridge would cut into their city’s increasing importance as a rail center. Political opponents mustered enough force for a congressional bill in 1865 that would limit the authorization to a bridge that “spans no less than five hundred feet and minimum clearance of fifty feet.” They were confident such requirements would doom the project.” They were wrong. 7.

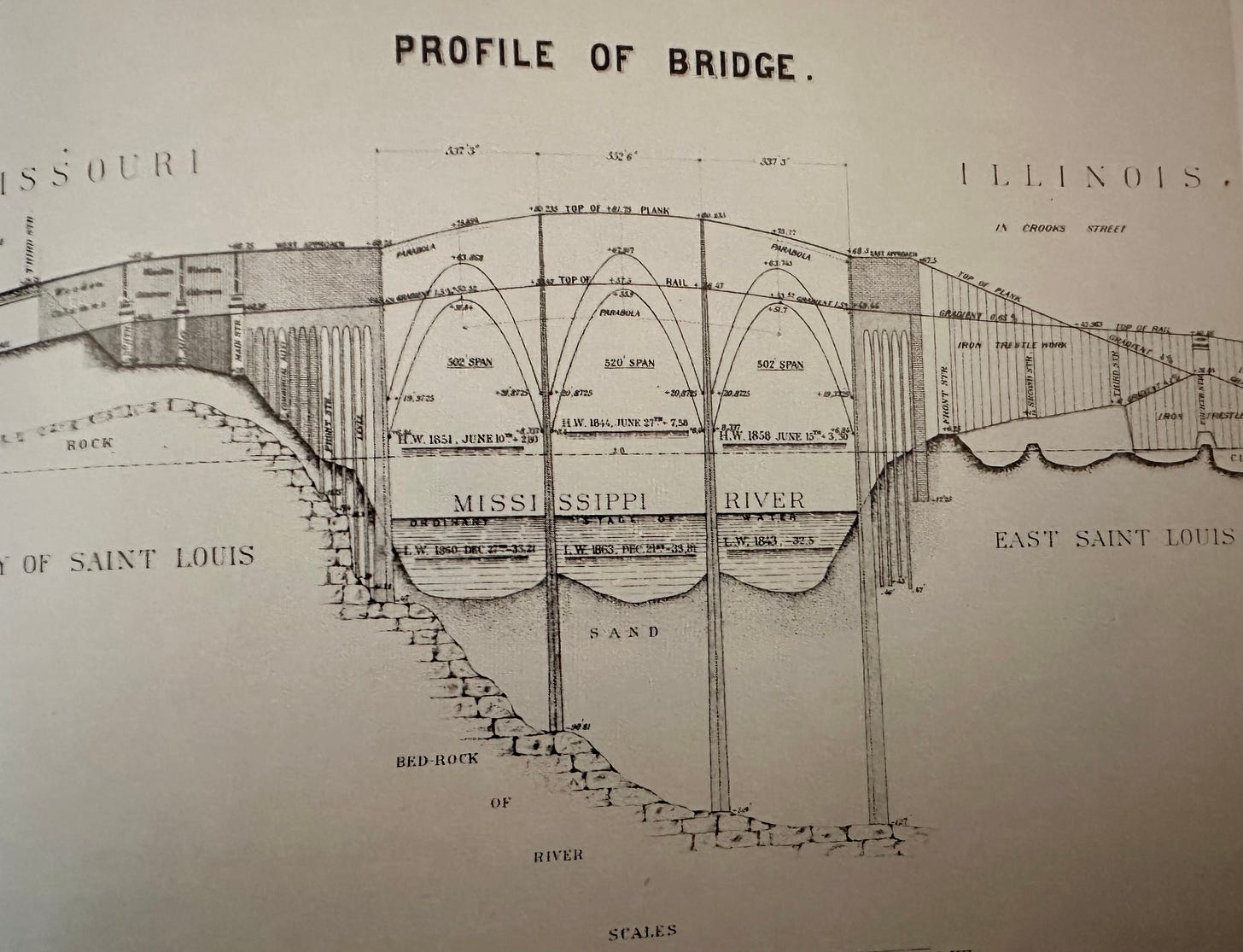

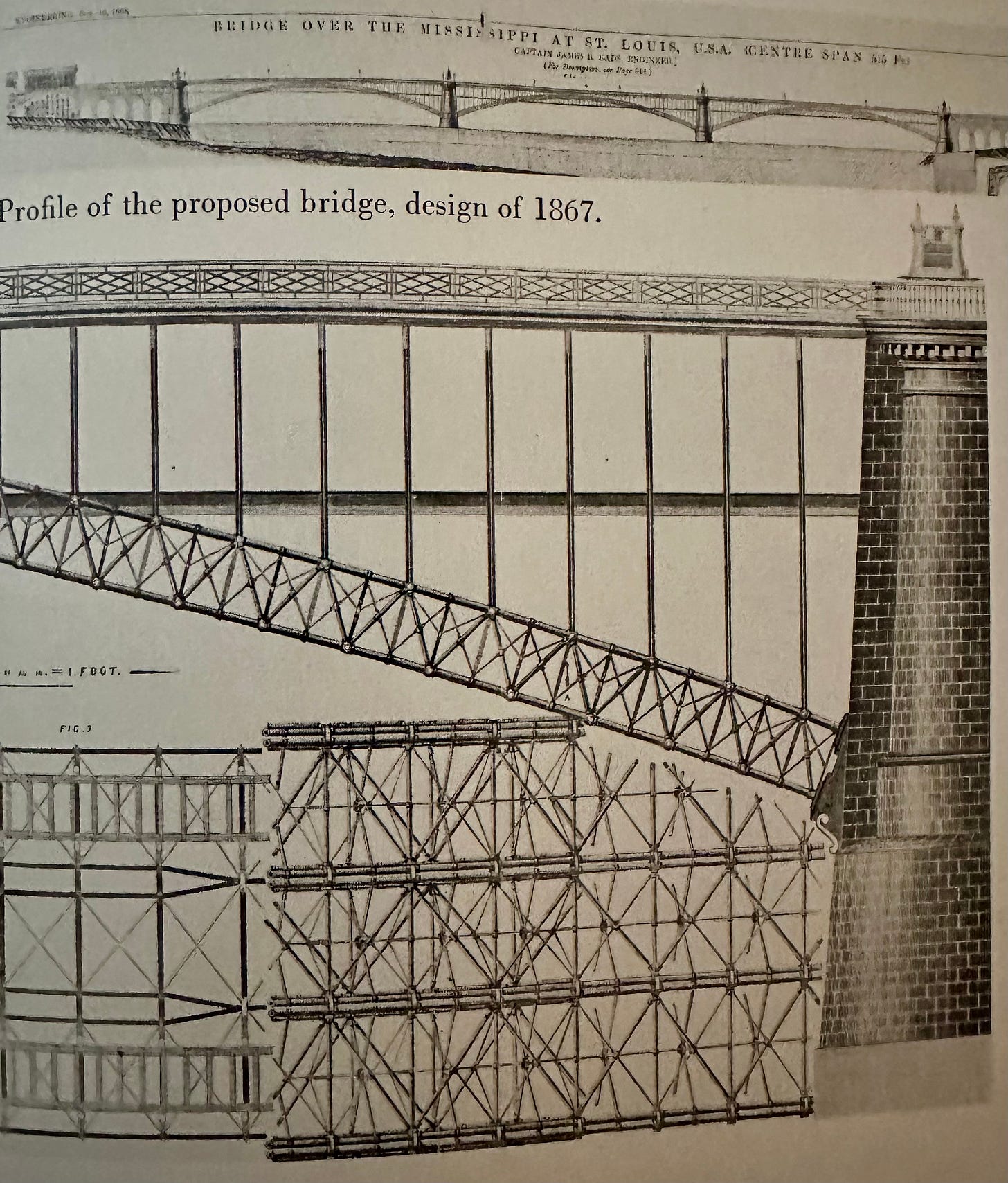

“Instead, Eads announced his unprecedented plans: ribbed arches with spans of 502, 520, and 502 feet made from a recently invented but as yet unproved alloy called steel were to be the main superstructure.

Cross section of the arched bridge. Circa 1867. The Eads Bridge by Howard Miller.

“The River itself posed the most difficult design problems, but these were problems Eads was uniquely equipped to solve. More than Lucius Bloomer (Chicago) or any other bridge promoters, Eads understood and respected the river’s turbulent currents, ice gorges and violent action. At the bridge site, the Mississippi was approximately fifteen hundred feet wide. Through this relatively narrow channel surged the runoff from a drainage basin of nearly seven million square miles. The velocity of the current ranged from four feet per second at low water to more than twelve at high water. At normal water stage, 1.68 million gallons passed by each second, while at full flood the discharge might be four times as great.” 8.

“Foundations were to be based on bedrock to ensure stability during spring floods and winter ice jams. On the basis of those preliminary plans, Eads was elected chief engineer of the St. Louis and Illinois Bridge Company.” 9.

Detail arches, design of 1867. The Eads by Howard S. Miller.

Eventually Eads won financing and contracts to build the first steel bridge in the United States. The paradigm shift from years of dealing with north vs south to a new era focused predominantly on commerce east to west was finally occurring. The new bridge wouldn’t burn or collapse. It would be solid and safe. It would support all traffic. Walkers, horse, buggy, wagon, motor coach. The Eads Bridge would support the abundant train commerce so necessary to connect the east and west, north and south. It was no longer necessary to run the northern route through Chicago when supplies were headed for the eastern seaboard, southern states or western territories. Traffic would no longer be halted or be re-routed when the Mississipppi flooded or froze. And river traffic could traverse the river under the bridge arches without difficulty.

ARCHES WITHIN ARCHES

Building the Eads Bridge, 1873: 2,390 tons of steel, 806 tons of timber, 218,000 tons of limestone block. From Great River City, by Andrew Wanko. West Pier, fall 1873. Boehl and Koenig, photographers. The Eads Bridge. Howard S. Miller

Closing the West Span. 1873. Robert Benecke, photographer. The Eads Bridge by Howard S. Miller

Beginning construction of the road Deck, spring 1874. Robert Boencke, photographer. The Eads Bridge by Howard S. Miller.

Eads Bridge completed, July 1874, Robert Boenecke, photographer. The Eads Bridge by Howard S. Miller.

Eads Bridge from the levee. Circa 1890. Photographer unknown. The Eads Bridge by Howard S. Miller.

The Eads Bridge arches by Howard S. Miller. Photo essay by Quinta Scott.

The Eads Bridge by Howard s. Miller. Photo essay by Quinta Scott.Circa 1970.

James Buchanan Eads

James Buchanan Eads was known as the greatest civil engineer of his time. The Eads Bridge was a phenomenon of design with functional structure and longevity.

Eads’ last bridge report as chief engineer reads “with great hope that usefulness, undoubted safety and beautiful proportions of the bridge would constitute it as a national pride, entitling those through whose individual wealth it has been created to the respect of their fellowmen; while its imperishable construction will convey the future ages a noble record of the enterprise and intelligence which mark the present times.” 10.

Although repairs to the stone and tracks have been required, the Eads Bridge is still in use despite political scourge, financial pressure and uncooperative jealousies during its enormous life span. Quality and safety were not shorted on THIS bridge. Most importantly, the community gave Eads’ hard work its due with a resounding support for the bridge. So much so that July 4th, 1874 six hundred thousand guests from around the world overwhelmed St. Louis to celebrate the country’s birthday and the grand opening of the Eads Bridge. It was the grandest gathering St. Louis had seen. Parties went on for days.

Less than 30 years later, the St. Louis World’s Fair (1904) exponentially multiplied those who had come to celebrate the Eads Bridge. Thousands of visitors traveled across the bridge, entered the city and made their way to meet in St. Louis for the first US Olympics, the first ice cream cone, and the most EXTRAORDINARY international display the world had ever seen.

Two of Eads’s Mississippi River works are still functioning today, serving people and commerce. The first project is Eads Bridge. The beauty and grace of its design continues to delight artists and photographers.

The second project is the jetties at South Pass, one hundred miles beyond New Orleans, at the end of the Mississippi delta. Following a great controversy with the Army Corps of Engineers, the jetties were constructed so the flow of the river keeps the channel from filling with silt. Ships continue to travel daily through this deep channel. 11.

Thank you for reading EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE, discussion with or about everyday people living EXTRAORDINARY lives. Please share with friends and family to suppport my work. IT’S FREE!

References:

1.Twain, Mark. Life on the Mississippi. Penguin Press. 1883 Miller,

2.Wanko, Andrew. Great River City, How the Mississippi Shaped St. Louis. Missouri Historical Society Press, St. Louis. 2019.Jackson, Robert W., Rails Across the Mississippi, A History of the St. Louis Bridge, University of Illinois, 2001.

3.4.11. Missouriencyclopedia.org

5.6.Wanko, Andrew. Great River City, How the Mississippi Shaped St. Louis. Missouri Historical Society Press, St. Louis. 2019.Jackson, Robert W., Rails Across the Mississippi, A History of the St. Louis Bridge, University of Illinois, 2001McGee, Ken. The Great Hope of the World. Ken McGee. 2017

7.https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/james-buchanan-eads/

8.9.10.11.Miller, Howard. Scott, Quinta. The Eads Bridge, University of Missouri Press, Columbia & London, 1979.

Thanks, Sara, for your research on James Buchanan Eads, a very extraordinary man! The history of steamboat piloting by Mark Twain was interesting and informative. The photos and history of the St Louis riverfront and of Eads submarine…amazing. It all tied together nicely. Thanks!